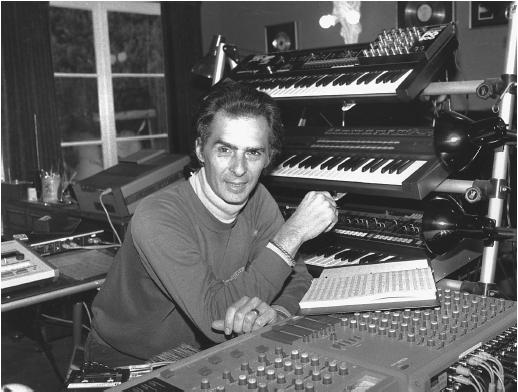

Aquí os queda una entrevista con Hans Zimmer, toda uná máquina en este mundo de las bandas sonoras.

Para quienes no lo sepais, es el autor de bandas sonoras tan reconocidas como Gladiator, Lágrimas del Sol, Pearl Harbour, El rey león... y muchas otras.

Esta es una entrevista de hace un tiempecillo, que os dejamos aquí en inglés.

Hemos partido la entrevista en dos, para no crear la Megaultrainfinita entrada, así que aquí os queda la primera parte:

Edwin Black: More soundtrack music is available today than ever before. In the '60s, when I first became fascinated with soundtrack music, you could purchase a dozen or so records per year. Now some 500 are released annually, more than one per day between new and re-released material. So there much more quantity coming out. But what about the quality?

Hans Zimmer: Within any year I see 90--no, maybe 98--percent horrible stuff and two percent quality.

B: Last year, what scores were that two percent quality?

Z: I'm not sure. But one I did actually like was The English Patient.

B: What about Starship Troopers?

Z: One great cue in there, I thought, was a slow string piece. It wasn't a big theme. I thought, wow, this is really great writing. I was much more impressed by that than all the bombastic stuff. As for me, I certainly didn't write anything great last year. B: If you didn't do anything great, what was the best you did do?

Z: Peacemaker. I liked one theme in it.

B: The "Sarajevo" theme?

Z: Yes, all that stuff around that thematic neighborhood. Because it was inspired. We all have craft, we all have technique. But the moments of inspiration, that's where it really happens for composers.

B: Are you saying the current filmmaking environment makes inspiration and innovation less possible?

Z: Right. For one, there's just too much music being used.

B: Remember the chase scene in Bullitt had no music.

Z: The fight in Rocky had no music either. I know that for a fact because a producer once said to me that he wanted the scene to sound like the Rocky fight and that my music was all wrong. I went out and got the video of Rocky and discovered the scene had no music.

B: John Barry recently scored Mercury Rising. He employed his traditional introspective commentary music for the action scenes. It wasn't all boom boom and blast.

Z: Right. And how many movies did John try that where they fired him because they didn't think it would work?

B: Two or three.

Z: At least. You hire John for exactly that thing which he does...and sometimes you must have a lot of courage.

B: If you hire John Barry for that thing that John Barry does, why do you hire Hans Zimmer?

Z: I have no idea. I'm this loose cannon--all over the place. I can do action movies and romantic comedies. And I'm a good collaborator--which means I'm cantankerous and opinionated. I compose from a point of view. Point of view is the most important thing to have, and it doesn't necessarily have to be the director's point of view. In fact, great directors welcome disagreement and bringing something new to the party. The bottom line is I'm trying to serve the film just like the director is trying to serve the film. A film takes on a life of its own, and you just hang on for dear life. Eventually, it starts talking back to you. It's an odd process.

B: So why so many action movie assignments?

Z: You know why I did all those action movies? Because when I was a kid in Europe, all I got to score was art movies. In those days, all I wanted to do was go to Hollywood, compose for action movies and sound like John Williams. But in truth I didn't know how. So Black Rain, my first action movie, was original but only by virtue of my own stupidity. My lack of knowledge made it original.

B: I've listened to the Black Rain CD 300 or 400 times. But I rented the video to check the music in some of my favorite scenes. You composed long cues, but they are used in the movie only for an instant.

Z: Would you like to know what happened? Our producer, Stanley Jaffe, at the time, hated everything I was doing. And hated it so much that I actually got shouted at after a screening at Paramount, and I fainted. So by the time we got to the dub stage, I was just living in fear. We were battling the system. And it's very odd because Monday night after the Oscars, I went to a little private party. Michael Douglas was there, and he said, "You really saved my ass in Black Rain." And I thought, "Wow, great. Thank you, Michael, you realized what I did."

B: But why isn't the Black Rain Suite in the final cut? You only hear a few seconds of a twenty-minute piece.

Z: Because it's always a war. Well, not always, but most of the time it's a war. You're in a battle and you lose faith and you lose heart--especially when your producer tells you that is the worst piece of music he's every heard.

B: And whose decision is it to pick up the editing knife?

Z: The director. In Black Rain, that was Ridley Scott. But Ridley was getting beat up as well.

B: So he's listening to the producer, Stanley Jaffe?

Z: We weren't listening to anybody anymore. We just couldn't catch our breath. In Thelma and Louise, Ridley used everything I wrote. In fact, he liked the theme that became "Thunderbird" so much that he tagged an opening with credits onto the film. Originally, credits were at the end. But he just wanted to hear that piece of music again. So, it's the same director working under completely different circumstances. In Thelma and Louise, it was just the two of us having the freedom to make our own decisions without getting crap kicked out of us.

B: Let's talk about the temp track, that is, the temporary score used during pre-screenings. Temp tracks have become controversial because so often they intrude into the final commissioned score.

Z: Yes, take As Good As It Gets--you can't temp it. They tried something, but it just didn't work. So I just started writing a score. Then we actually previewed my score in front of an audience to find out if it worked. We wouldn't say: "Pay attention to the score." We would just see how the movie progressed. Would it answer emotional questions for the audience, or would there be criticism of certain scenes.

B: When does the preconceived notion of the director intrude into your creativity?

Z: This is a very real problem. In As Good as It Gets, for example, I ultimately managed to dissuade the director Jim Brooks from every expectation. He said write a big romantic Americana score, and I wrote a small European score. You know, it depends on who you work with. If you do a big action movie, I suppose you're stuck. It's very hard to reinvent that form.

B: K2 was your only rejected film score?

Z: K2 was an odd thing. Someone else scored the movie, then my good friend, Franc Roddam asked me to rescore it. They ended up making lots of picture changes, so my score only made it to the European territories, and different versions went to the Japan and American territories.

B: When the score is not accepted, is the composer paid and free to take it elsewhere?

Z: The rule is you must be fired. You can't quit. If you quit, you don't get to pass GO. If you're fired you get paid.

B: Then you walk with the score?

Z: No, you don't walk with the recording because they paid for that.

B: I'm reminded of the original music to Prince of Tides by John Barry which was rejected and eventually became the beautiful score to Across the Sea of Time.

Z: I'm reminded of Randy Newman's (rejected) score for Air Force One. I heard it and said, "I have never written an action cue as good as this. And I'm supposed to be good at action stuff." Jerry Goldsmith did the replacement score. But When I saw the movie, I kept howling with laughter throughout the film. It was so patriotic. I don't know, it wasn't my cup of tea.

B: A bit too violent.

Z: No, it wasn't even the violence. It was all that overdone patriotism. I just thought it was hilarious. And I know that as a cynic, Randy's patriotic themes reflected a twinkle in the corner his eye. But I think they caught him at it. And the one thing you can't do when you're being cynical or satirical, is get caught at it. I should know. I got caught atit big-time in Broken Arrow. But I wanted to be caught. I didn't think we could sell an audience this bill of goods as a serious movie.

B: I seemed to be hearing some Ennio Morricone in there.

Z: Absolutely. But that's because I thought we were doing a Western! (laughs)

B: And Morricone's style goes back to Dimitri Tiomkin--High Noon. Morricone was just selling the American cowboy film back to us in the form of the spaghetti western.

Z: Yes. In Broken Arrow, we used that style because it was "big man" music. The guitar sound as well. I always thought Ennio wanted to work with Duane Eddy. So I just got the real Duane Eddy. In the score, you'll hear him plucking away. And it was great fun. And I know people got very worried about the music during the previews. I remember at one showing, in the third act when Travolta comes back--he should have been dead by the second act--and the little guitar tune comes in. The audience actually laughed--in a good way. They knew I wasn't being patronizing, thinking the audience was an idiot. My intent was just make the film fun, when there's no real story to tell. Well, I guess there was a story about betrayal between two men who've been friends forever. But that's not really what the movie was about. It was about blowing up a lot of things.

B: Your shop of multiple composers, known as Media Ventures, is something new in the field. Major composers always had their own team. Media Ventures, however, is larger, more diverse, employing composers in their own right, such as Harry Gregson-Williams and Mark Mancina, composers who receive their own screen credits. Yet your musical signature is undeniably there heard in most of the work. When directors offer projects to Media Ventures, who in truth is being retained, Hans Zimmer or the other composers?

Z: It depends. Media Ventures is larger, but only for one really stupid reason. It started this way: when you are European wanting to break into the Hollywood film business you don't stand a chance. But Barry Levinson gave me a shot in Rain Man, and that was very gracious and courageous. Then I knew all these other composer friends who never got a shot at anything. Just because I'd done a few successful films, director and producers felt safe, like I could pull rabbits out of hats. So I just dragged some of my friends in and tried to get their careers off the ground as well. And why? Out of the most stupid reason: I really like hearing their music--people like John Powell, Harry Gregson-Williams, Mark Mancina. But it's true, we always have to watch out, that everything doesn't sound like me.

B: I just heard Replacement Killers, which Gregson-Williams scored. I'm hearing good original music. But I am also hearing sections that are kissing cousins to Peacemaker, which you wrote.

Z: Yes, the problem is that the whole sound starts to get identifiable.

B: Inevitably, the questions is, is it a collaboration or is one guy going into a cave to score?

Z: He's scoring in a cave. For Replacement Killers, I didn't even hear what he was doing. I mean, we all talk a lot together about our projects. For instance, John is working on Endurance, a film Terry Malick is producing. At the same time, I'm working on Thin Red Line, a film Terry Malick is directing. Endurance is nothing I could possible write. It's as far from my style as you can possibly get.

B: So how much of you is in The Rock which has a mishmash of music credits?

Z: The main theme is mine, as are a few other bits. It's really hard to tell. I do have a huge influence in there. But I never really wanted to write any of it. It was always supposed to be Nick Glennie-Smith's score.

B: I heard this was a rescue job on a score started by another composer. How much time were you allotted for the rescue?

Z: None, it seems. I think I must have worked four weeks around the clock.

B: Was this the shortest time you ever had to work on a piece?

Z: No. It was the rescore for White Fang. I don't think I even have a credit on it, but I probably wrote 80 minutes of music in 16 days. It was sort of a dare that producer Jeffrey Katzenberg threw at me. And I was foolish enough to say yes. I delivered, and never told Jeffrey I was sick as a dog for two weeks afterwards. But when you're a kid you take on any old dare. You know, Lion King was short, it took about three and a half weeks.

FIN DE LA PRIMERA PARTE