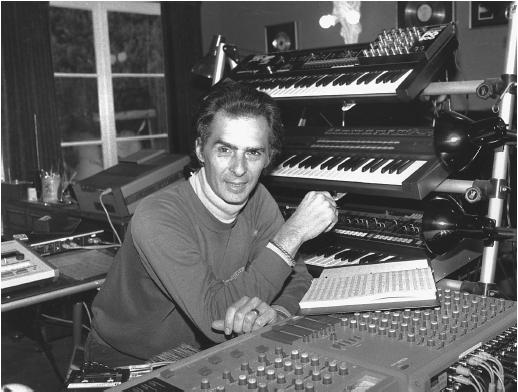

La película de esta semana es de este galardonado autor. Hay varias películas conocidas en las que escuchamos sus obras, pero hasta el miércoles nada amiguetes.

La entrevista es de hace un tiempo y quizás no se relacione mucho con nuestro film, además la dejamos en inglés.

Si os veis con problemas a la hora de entender lo que dice, tenéis un traductor en la propia página de www.google.es , algo básico, pero suficiente. Además existen multitud de traductores online, solo es cuestión de buscarlos.

Esperamos que sea interesante, por cierto quien hace la entrevista es Daniel Schweiger, ¿os suena de algo?

DS: Did you actively pursue The Thomas Crown Affair?

BC: I know it's a stock-in-trade to do that, but I don't pursue films at this point in my life. But it's mildly interesting how I got the job. Pierce Brosnan made a film with John McTiernan called Nomads, for which I did the score. It was John's first picture. He remembered me, and called me to do The Thomas Crown Affair. I had seen the original picture and adored it.. So why do they do remakes like this? I have no idea. I did the original Gloria, which wasn't even a hit. But since Pierce was a producer on Thomas Crown, I'd say that he had something to do with remaking it.

DS: How do you get Michel Legrand's score out of your head?

BC: If John McTiernan made a Thomas Crown Affair that was a homage to the original, then I'd have to be conscious of the original score. Michel's score for the original defined an era. But is this a "90's" score? I wouldn't be able to give you an answer. This is a different film. It just has the same name. In my opinion, it could be called many other different things than The Thomas Crown Affair. It's not the same caper, but some story points are similar. If I want to say dark and light, I'd say this one is lighter in its tonal quality.

DS: Tell me about your score.

BC: I scored the film with two thoughts. One came from the opening titles. As a wink to the original, Faye Dunaway plays Pierce's psychiatrist. These lyrical title cards are going on during their conversation. There was a flow, and lyricism to them that I heard. That's my job. It's not a miracle or a mystery. I do that, because I know the language of music. Those things affect me musically, and I told John 'Wow, I really like this. As a matter of fact, I heard the whole thing. I'll let you hear it tomorrow morning.' And that's what I did. I went home, and started messing around with pianos, and ended up with five of them. I brought the music to John, and he liked it. I also have a string orchestra and a percussion section to reflect the slick nature of Thomas Crown. He's like a tap dancer, so you hear tap dancers on the percussion tracks. Those two ideas brought me the entire score.

DS: How did you come up with the tap dancing analogy?

BC: The guy's doing a caper. He's slick. But that tap dancing is subtle, as is the whole movie. The director and actors are winking at us. They don't want us to take the film too seriously. They want us to have fun. There are no gun or car chases, but you sit there and enjoy the movie.

DS: Are there any jazz touches to the score?

BC: There are jazz touches to the score, but I wouldn't call them "real" jazz. Real jazz is improvised. Michel's score was also written, but there are moments of improvisation in his score and mine. I think my score has a unique sound because of the five pianos. But to everyone else, it will sound like a really large piano, even though a pianist couldn't play all of those notes. The score is subtle, and interesting.

DS: Did John have anything he wanted your score to do?

BC: He knew what his movie was, and wanted the audience to be prepared for. So it would've been wrong if I scored The Thomas Crown Affair like an action picture. While there are moments of tension, you aren't going to think that an explosion's going to happen. There's a subtlety of entertainment, fun, intelligence and sophistication. It's not a movie for people who are expecting vulgarity. The score can't do the vulgarity of "He's a bad guy, he's a good guy, here's the chase and this is the sex." In the Greek chorus style, the score is supposed to be as sophisticated as the movie is. Hopefully, I've done that.

DS: What do you think equals musical sophistication?

BC: You'd have to begin by talking about what unrefined music is. It's anything that has rock and roll, rap and repetitive rhythm and harmony. The guy who drinks ripple instead of wine would not expect a sophisticated composer like Mozart. And the guy who's drinking ripple doesn't even know that he's vulgar. They don't get it. You need to acquire sophistication. It's an aesthetic that transcends words and takes your breath away. You have to be educated to know a real kind of sophistication, because the ordinary person just wouldn't get it. You can get a high with a bottle of Ripple, but the explosion of your taste buds with fine wine is like a bigger orgasm.

DS: How many themes are in your score?

BC: There's a dark and a light theme. One that tells you something's happening, and one that tells you people are having fun. Those two themes are all about Mr. Crown. Catherine has a theme which is more emotional. Her character is more complex than Crown's. There are other thematic things in the score, but they're so inside that they don't come across as being thematic.

DS: Are there any other instrumental motifs in the score?

BC: Beyond the pianos and the tap dancing, there's a Nina Simone recording which is used during a very critical part of the movie. It's very effective, and came from a great idea that John had. There's also a cameo appearance of the song "The Windmills of Your Mind," which shows up with Faye Dunaway. I didn't have a problem with that. After all, wouldn't you want to hear that with her character?

DS: What was your collaborative process like with John?

BC: Music is anti-intellectual. It's non-literal, and you have to find out what makes the director happy. You want to let someone hear what you're thinking about. Because if you get to the stage, and the director says "I wasn't thinking like that," then your score won't be in the movie. But we didn't have that kind of collaboration, because it just didn't work out that way. John was very busy, and lived in Wyoming. He never came to my house. He only listened to the main title, then he heard the rest of the music on the scoring stage. When John had a problem, I re-manipulated my material.

DS: How did you get into film scoring?

BC: I always wanted to write dramatic music. Maybe that's because I came from a house where Italian opera was always being played. It made me want to be a Baroque composer, and I wanted to get paid to write that kind of music. In the back of your mind, when you say you want to write music for the movies, you're saying that you want a big house, a big car and a boat. If you just wanted to write music, you could live in Kansas and do it. So how can you be a professional composer? You can teach school and write. But that's not being a professional composer, is it? You can only live on Guggenheim grants and Fullbright scholarships for a while. But how do you become a "real" composer? You have to go into the commercial world, which isn't unlike what the Baroque composers did. Cobblers made shoes. Mozart's job classification was to write music, which he did for ballets and operas. He got paid to do that, and taught on the side. He wasn't a waiter. He didn't sell mutual funds. Those are all noble professions, but if you want to be a professional composer, then you're writing dramatic music for film and television. And it's a wonderful thing to do that every day, rather than writing music for a one-time performance. Benjamin Britten disagreed with Penderecki, who was a contemporary of his. Penderecki wrote for 2,000 informed people in the world. People who knew the difference between champagne and ripple. Britten said "I'm a member of the social community. I write for people. And if they're rejecting my music, then I'm writing the wrong kind of music." So if you're a member of the community, then one of the legitimate professions is being a film composer. And I always wanted to do that. I wanted to write thematic music, and get paid for it. And if you're in LA, you get the Hollywood bug. You want the same things that everyone else has- a lawyer, a business manager, an agent, a publicist, and big, big bucks. It's sick, but that's the ideal. So you pursue that. And if you're lucky, you catch the gold ring.

DS: How do you keep yourself in the Hollywood game?

BC: Who wants to be in the game? How much money do you want? I did a couple of things. I've got an Academy Award, an Emmy and some hit songs. On the academic side, I've got two Bachelors, a Masters and a Doctorate. Do you care? And you shouldn't care. What's it all in the pursuit of? I'm fine.

DS: Do you think there's a rediscovery going on now of older composers like yourself?

BC: I think the history of film music writing begins with the Viennese composers. Schoenberg wasn't a film composer, and he wrote great music. So who wrote film music? Guys who were pretty good, but guys who had no illusions of being "A" composers. My music goes towards an end, which is a movie. From the early days of film scoring, there were guys who were educated in music. There were okay writers, and there were guys who didn't have a clue. They were the brothers of, the cousins of the guy who had the real job, and he used other people to write his music, then put his name on it. That's back in the beginning of the "good old, Golden Age" days. So what's different about it from the 30's to the 90's? Nothing. You could say "style," but men still wear long pants. The personality types of the composers are the same. There are guys who know how to write pretty good, but they're not Stravinsky. Aaron Copland did a movie or two, but we don't know him as a film composer. There are guys who know how to be effective. But what does "effective" mean? The Creature From the Black Lagoon jumps up, and the music scares me. But is that "music?" Who cares? It scared me. So the guy who's equally uninformed, whether he's the producer or the director, wants the composer who's effective, because he doesn't have to be musically literate. That's not his job. He just has to be musically effective for the director. There are guys who walk away with Academy Awards who don't know how to write a note of music. You would think that would be a prerequisite in the biz, but it's not. And I'm not saying that in a bad way. I think it's great. There are no illusions about being more than who you are as a composer. If you can effectively put something musical in the right place, then you've got the job and the big bucks. So it's not about being young and in fashion. I see Jerry Goldsmith doing another score, and he's not getting any younger, or doing any less work. So "youth" hasn't impinged on his desire. Does he need the money? I hope not. Does he need fame? I'm sure he does.. Seneca said "What's the sense of saving journey money when the journey's getting shorter? How much journey money do you really need?" And I was a workhorse. I loved to write music, and I wrote it for fifteen years in a row for everything, anything, anywhere. And then I said "I'm tired of that. I just don't want to do that anymore." It left me.

DS: Well, I think it's great that you're doing a big studio film. It's the first one you've done in a while. You should be doing more of them.

BC: Making a living is not a career. It might be for an accountant, but it's not for someone who says "I want one thing." The guy who feels that his career hasn't happened yet. The guy who has that kind of hunger, who wants money and fame. If your career's going to reach a plateau, than you're going to cop to any of these things. I think John Williams and John Barry have five Academy Awards. Do they want number six? I don't know. But do I want number two? Sort of. It would be a lie to say that I didn't.

DS: It would be nice to be conducting your own music at the Academy Awards if you won another one.

BC: I've conducted twice when I've lost. I was up for Rocky and For Your Eyes Only when I had to play someone else's music. And the only time I sat in the audience during fourteen years of going, I won for The Right Stuff. It's a rush to do the show. It's all about being able to do live music well, and I love it. But I was as bored and anxiety-ridden as everyone else when I was sitting in the audience, the one year when I wasn't conducting. And I won! That was kind of neat.

DS: With so many scores behind you, don't you think you should be better-represented on CD?

BC: I get lots of requests for The Big Blue, Gloria and The Karate Kid. And I think, "what a bore." The only time I've put out CDs were for these three IMAX pictures, The Grand Canyon, Yellowstone and Niagara Falls. They sell at the parks, and I retained the rights for the music. So that means I went into the CD business. Somebody prints them up, stamps them, and mails them out. I hate every inch of the thought of doing that, because I don't want to be a businessman. So why did I do that? I did it as an experiment. Forget money. If 10, or 100 thousand people want The Big Blue, it don't mean a thing. It needs to be a hit. Maybe your little composer ego goes "Wow!" But I can't tell you how many Yellowstone CDs have even been sold. It's just irrelevant. So when people ask for a tape of Gloria, I tell them that I'm sorry, but I'm not in the business of making tapes. They should just consider the music as not being released. I only wish there was a hit. I don't want to know Gloria. Who cares?

DS: A lot of your fans do. Shouldn't it feel good that people want your music?

BC: You're right. It should feel good, but it's always been cumbersome to put out CDs of my scores. I don't even have any tapes of mine. I don't have a clue of where they are, or records of where they went to. But knowing that there are people out there who do care, the thought has crossed my mind to hire someone to start a label. But then there are those sleazy boutique labels that put out bootlegs. I don't want to be a shopkeeper. Even if I hired someone, wouldn't I still be the shopkeeper?

DS: What do you think of your CD for Blood In Blood Out (retitled Bound by Honor ) going for hundreds of dollars on the collector market?

BC: I don't even have a copy. The soundtrack didn't come out when the film wasn't a hit, and I felt really bad about it. When the film dies, the record dies. Unless the score is going to fly with a hit song, it's not going to reach the people who care about it. It's not a big ticket item. The same thing happened with The Right Stuff. I had a record deal with the Ladd Company, and I'd even mixed the album. The film didn't do business, and they didn't put out the album. So I put out $20,000 when I was recording another movie in London, and I re-recorded North and South with The Right Stuff. Then the record company reimbursed me.

DS: Do you think there's a common bond that runs through your scores?

BC: Me analyzing me is not the same as someone else listening to me. But I think there's always a melodic content in my music. I love melody. There's some sort of Italian-ate lyricism to what I do because of my operatic background. And I don't want my music to be part of the woodwork. Some people say "A good score is if you don't hear it." Then why don't you just say "Let's have the actors mumble." Why does a door slam have to sound like World War III? Why does a gunshot have to be bigger than any gunshot I've ever heard in my life? I want my music to be heard, and if you don't hear my scores, then I've failed. But I also don't want my music to be thrown out if the director feels that I'm taking attention away from the movie. The director is the captain of the ship. He can tell a writer to punch up the dialogue. He can make the lighting brighter. But when it gets to the music, the director is left saying something like "I want it to feel blue." What does that mean? Music isn't literal, it's dangerous. It can sneak up on you and do things. So you're fighting this psychological drama to get into the head of the captain of your ship, because he just can't do it. A director can control everything- except music. He understands it on the only level he should, an emotional one. And if the music doesn't work for him, it ain't working. There was a cue I did for The Thomas Crown Affair that had the room jumping up and down. But I said to John, "Look, if it doesn't work for you, it doesn't work. Let me do it differently." And I reached, and found what was missing for John so he could jump on the bandwagon. It's tough. The music is best if it's held down. It's more dangerous if it's loud.

DS: Your theme for Rocky is your most popular piece of music. What's it like to achieve that level of public consciousness?

BC: That kind of phenomenon happens when there's the coordination of people liking the movie and your music, and it being a hit. I've been fortunate to be on that ride. It didn't have to happen. But It did, and I'm thankful.

DS: You've scored films with a wide variety of styles, from jazz to Americana. Is there any style of music that you'd still like to explore?

BC: I just want to write pretty, melodic music. I haven't done something pretty and quiet in so long. But I've cut back anyway. I'm not doing as much. Most recently I did a picture called Winchell for Paul Mazursky and Inferno for Jean-Claude Van Damme. But I've felt a lack of scores like Slow Dancing In the Big City. The aggressive, macho, punch-in-the-face had its timespan in the 70's. And it's difficult to look away from a gift horse. But at least that punch-in-the-mouth stuff happened! And I can do the Rocky and Right Stuff styles when people want me to. But pretty, slow, sad music is what I want to do.

DS: Where do you want your music to stand in the grand scheme of film scores?

BC: It has to stand only as film music for sure. Remember, my opinion of it is not that high. It began with three Viennese composers, and Korngold is not Richard Strauss. He's not as good as him. Strauss' Salome is wonderful. Korngold, in his operas and his film scores are not to be said in the same breath as Richard Strauss. However, Korngold is probably one of the best film composers who ever lived! Franz Waxman, Max Steiner, they're great film composers. And if I could be part of a good group of film composers, then that would be nice. But there's a higher place that I have no illusions about reaching. There's a sophistication and aesthetic about composers who only write only for the music's sake. I don't follow the muse. I follow the film. I watch the opening of The Thomas Crown Affair, and the music feels a particular way, because that's the way I heard it. Is that a muse moment? Who knows, because it was inspired by the film, and that's what I do. I don't want it to sound like I'm putting film scoring down. I'm just being objective about the level that I'm at. Those pure composers are higher, better than me. I'm ripple, and they're big-time wine. But we still do the same things.

La entrevista es de hace un tiempo y quizás no se relacione mucho con nuestro film, además la dejamos en inglés.

Si os veis con problemas a la hora de entender lo que dice, tenéis un traductor en la propia página de www.google.es , algo básico, pero suficiente. Además existen multitud de traductores online, solo es cuestión de buscarlos.

Esperamos que sea interesante, por cierto quien hace la entrevista es Daniel Schweiger, ¿os suena de algo?

DS: Did you actively pursue The Thomas Crown Affair?

BC: I know it's a stock-in-trade to do that, but I don't pursue films at this point in my life. But it's mildly interesting how I got the job. Pierce Brosnan made a film with John McTiernan called Nomads, for which I did the score. It was John's first picture. He remembered me, and called me to do The Thomas Crown Affair. I had seen the original picture and adored it.. So why do they do remakes like this? I have no idea. I did the original Gloria, which wasn't even a hit. But since Pierce was a producer on Thomas Crown, I'd say that he had something to do with remaking it.

DS: How do you get Michel Legrand's score out of your head?

BC: If John McTiernan made a Thomas Crown Affair that was a homage to the original, then I'd have to be conscious of the original score. Michel's score for the original defined an era. But is this a "90's" score? I wouldn't be able to give you an answer. This is a different film. It just has the same name. In my opinion, it could be called many other different things than The Thomas Crown Affair. It's not the same caper, but some story points are similar. If I want to say dark and light, I'd say this one is lighter in its tonal quality.

DS: Tell me about your score.

BC: I scored the film with two thoughts. One came from the opening titles. As a wink to the original, Faye Dunaway plays Pierce's psychiatrist. These lyrical title cards are going on during their conversation. There was a flow, and lyricism to them that I heard. That's my job. It's not a miracle or a mystery. I do that, because I know the language of music. Those things affect me musically, and I told John 'Wow, I really like this. As a matter of fact, I heard the whole thing. I'll let you hear it tomorrow morning.' And that's what I did. I went home, and started messing around with pianos, and ended up with five of them. I brought the music to John, and he liked it. I also have a string orchestra and a percussion section to reflect the slick nature of Thomas Crown. He's like a tap dancer, so you hear tap dancers on the percussion tracks. Those two ideas brought me the entire score.

DS: How did you come up with the tap dancing analogy?

BC: The guy's doing a caper. He's slick. But that tap dancing is subtle, as is the whole movie. The director and actors are winking at us. They don't want us to take the film too seriously. They want us to have fun. There are no gun or car chases, but you sit there and enjoy the movie.

DS: Are there any jazz touches to the score?

BC: There are jazz touches to the score, but I wouldn't call them "real" jazz. Real jazz is improvised. Michel's score was also written, but there are moments of improvisation in his score and mine. I think my score has a unique sound because of the five pianos. But to everyone else, it will sound like a really large piano, even though a pianist couldn't play all of those notes. The score is subtle, and interesting.

DS: Did John have anything he wanted your score to do?

BC: He knew what his movie was, and wanted the audience to be prepared for. So it would've been wrong if I scored The Thomas Crown Affair like an action picture. While there are moments of tension, you aren't going to think that an explosion's going to happen. There's a subtlety of entertainment, fun, intelligence and sophistication. It's not a movie for people who are expecting vulgarity. The score can't do the vulgarity of "He's a bad guy, he's a good guy, here's the chase and this is the sex." In the Greek chorus style, the score is supposed to be as sophisticated as the movie is. Hopefully, I've done that.

DS: What do you think equals musical sophistication?

BC: You'd have to begin by talking about what unrefined music is. It's anything that has rock and roll, rap and repetitive rhythm and harmony. The guy who drinks ripple instead of wine would not expect a sophisticated composer like Mozart. And the guy who's drinking ripple doesn't even know that he's vulgar. They don't get it. You need to acquire sophistication. It's an aesthetic that transcends words and takes your breath away. You have to be educated to know a real kind of sophistication, because the ordinary person just wouldn't get it. You can get a high with a bottle of Ripple, but the explosion of your taste buds with fine wine is like a bigger orgasm.

DS: How many themes are in your score?

BC: There's a dark and a light theme. One that tells you something's happening, and one that tells you people are having fun. Those two themes are all about Mr. Crown. Catherine has a theme which is more emotional. Her character is more complex than Crown's. There are other thematic things in the score, but they're so inside that they don't come across as being thematic.

DS: Are there any other instrumental motifs in the score?

BC: Beyond the pianos and the tap dancing, there's a Nina Simone recording which is used during a very critical part of the movie. It's very effective, and came from a great idea that John had. There's also a cameo appearance of the song "The Windmills of Your Mind," which shows up with Faye Dunaway. I didn't have a problem with that. After all, wouldn't you want to hear that with her character?

DS: What was your collaborative process like with John?

BC: Music is anti-intellectual. It's non-literal, and you have to find out what makes the director happy. You want to let someone hear what you're thinking about. Because if you get to the stage, and the director says "I wasn't thinking like that," then your score won't be in the movie. But we didn't have that kind of collaboration, because it just didn't work out that way. John was very busy, and lived in Wyoming. He never came to my house. He only listened to the main title, then he heard the rest of the music on the scoring stage. When John had a problem, I re-manipulated my material.

DS: How did you get into film scoring?

BC: I always wanted to write dramatic music. Maybe that's because I came from a house where Italian opera was always being played. It made me want to be a Baroque composer, and I wanted to get paid to write that kind of music. In the back of your mind, when you say you want to write music for the movies, you're saying that you want a big house, a big car and a boat. If you just wanted to write music, you could live in Kansas and do it. So how can you be a professional composer? You can teach school and write. But that's not being a professional composer, is it? You can only live on Guggenheim grants and Fullbright scholarships for a while. But how do you become a "real" composer? You have to go into the commercial world, which isn't unlike what the Baroque composers did. Cobblers made shoes. Mozart's job classification was to write music, which he did for ballets and operas. He got paid to do that, and taught on the side. He wasn't a waiter. He didn't sell mutual funds. Those are all noble professions, but if you want to be a professional composer, then you're writing dramatic music for film and television. And it's a wonderful thing to do that every day, rather than writing music for a one-time performance. Benjamin Britten disagreed with Penderecki, who was a contemporary of his. Penderecki wrote for 2,000 informed people in the world. People who knew the difference between champagne and ripple. Britten said "I'm a member of the social community. I write for people. And if they're rejecting my music, then I'm writing the wrong kind of music." So if you're a member of the community, then one of the legitimate professions is being a film composer. And I always wanted to do that. I wanted to write thematic music, and get paid for it. And if you're in LA, you get the Hollywood bug. You want the same things that everyone else has- a lawyer, a business manager, an agent, a publicist, and big, big bucks. It's sick, but that's the ideal. So you pursue that. And if you're lucky, you catch the gold ring.

DS: How do you keep yourself in the Hollywood game?

BC: Who wants to be in the game? How much money do you want? I did a couple of things. I've got an Academy Award, an Emmy and some hit songs. On the academic side, I've got two Bachelors, a Masters and a Doctorate. Do you care? And you shouldn't care. What's it all in the pursuit of? I'm fine.

DS: Do you think there's a rediscovery going on now of older composers like yourself?

BC: I think the history of film music writing begins with the Viennese composers. Schoenberg wasn't a film composer, and he wrote great music. So who wrote film music? Guys who were pretty good, but guys who had no illusions of being "A" composers. My music goes towards an end, which is a movie. From the early days of film scoring, there were guys who were educated in music. There were okay writers, and there were guys who didn't have a clue. They were the brothers of, the cousins of the guy who had the real job, and he used other people to write his music, then put his name on it. That's back in the beginning of the "good old, Golden Age" days. So what's different about it from the 30's to the 90's? Nothing. You could say "style," but men still wear long pants. The personality types of the composers are the same. There are guys who know how to write pretty good, but they're not Stravinsky. Aaron Copland did a movie or two, but we don't know him as a film composer. There are guys who know how to be effective. But what does "effective" mean? The Creature From the Black Lagoon jumps up, and the music scares me. But is that "music?" Who cares? It scared me. So the guy who's equally uninformed, whether he's the producer or the director, wants the composer who's effective, because he doesn't have to be musically literate. That's not his job. He just has to be musically effective for the director. There are guys who walk away with Academy Awards who don't know how to write a note of music. You would think that would be a prerequisite in the biz, but it's not. And I'm not saying that in a bad way. I think it's great. There are no illusions about being more than who you are as a composer. If you can effectively put something musical in the right place, then you've got the job and the big bucks. So it's not about being young and in fashion. I see Jerry Goldsmith doing another score, and he's not getting any younger, or doing any less work. So "youth" hasn't impinged on his desire. Does he need the money? I hope not. Does he need fame? I'm sure he does.. Seneca said "What's the sense of saving journey money when the journey's getting shorter? How much journey money do you really need?" And I was a workhorse. I loved to write music, and I wrote it for fifteen years in a row for everything, anything, anywhere. And then I said "I'm tired of that. I just don't want to do that anymore." It left me.

DS: Well, I think it's great that you're doing a big studio film. It's the first one you've done in a while. You should be doing more of them.

BC: Making a living is not a career. It might be for an accountant, but it's not for someone who says "I want one thing." The guy who feels that his career hasn't happened yet. The guy who has that kind of hunger, who wants money and fame. If your career's going to reach a plateau, than you're going to cop to any of these things. I think John Williams and John Barry have five Academy Awards. Do they want number six? I don't know. But do I want number two? Sort of. It would be a lie to say that I didn't.

DS: It would be nice to be conducting your own music at the Academy Awards if you won another one.

BC: I've conducted twice when I've lost. I was up for Rocky and For Your Eyes Only when I had to play someone else's music. And the only time I sat in the audience during fourteen years of going, I won for The Right Stuff. It's a rush to do the show. It's all about being able to do live music well, and I love it. But I was as bored and anxiety-ridden as everyone else when I was sitting in the audience, the one year when I wasn't conducting. And I won! That was kind of neat.

DS: With so many scores behind you, don't you think you should be better-represented on CD?

BC: I get lots of requests for The Big Blue, Gloria and The Karate Kid. And I think, "what a bore." The only time I've put out CDs were for these three IMAX pictures, The Grand Canyon, Yellowstone and Niagara Falls. They sell at the parks, and I retained the rights for the music. So that means I went into the CD business. Somebody prints them up, stamps them, and mails them out. I hate every inch of the thought of doing that, because I don't want to be a businessman. So why did I do that? I did it as an experiment. Forget money. If 10, or 100 thousand people want The Big Blue, it don't mean a thing. It needs to be a hit. Maybe your little composer ego goes "Wow!" But I can't tell you how many Yellowstone CDs have even been sold. It's just irrelevant. So when people ask for a tape of Gloria, I tell them that I'm sorry, but I'm not in the business of making tapes. They should just consider the music as not being released. I only wish there was a hit. I don't want to know Gloria. Who cares?

DS: A lot of your fans do. Shouldn't it feel good that people want your music?

BC: You're right. It should feel good, but it's always been cumbersome to put out CDs of my scores. I don't even have any tapes of mine. I don't have a clue of where they are, or records of where they went to. But knowing that there are people out there who do care, the thought has crossed my mind to hire someone to start a label. But then there are those sleazy boutique labels that put out bootlegs. I don't want to be a shopkeeper. Even if I hired someone, wouldn't I still be the shopkeeper?

DS: What do you think of your CD for Blood In Blood Out (retitled Bound by Honor ) going for hundreds of dollars on the collector market?

BC: I don't even have a copy. The soundtrack didn't come out when the film wasn't a hit, and I felt really bad about it. When the film dies, the record dies. Unless the score is going to fly with a hit song, it's not going to reach the people who care about it. It's not a big ticket item. The same thing happened with The Right Stuff. I had a record deal with the Ladd Company, and I'd even mixed the album. The film didn't do business, and they didn't put out the album. So I put out $20,000 when I was recording another movie in London, and I re-recorded North and South with The Right Stuff. Then the record company reimbursed me.

DS: Do you think there's a common bond that runs through your scores?

BC: Me analyzing me is not the same as someone else listening to me. But I think there's always a melodic content in my music. I love melody. There's some sort of Italian-ate lyricism to what I do because of my operatic background. And I don't want my music to be part of the woodwork. Some people say "A good score is if you don't hear it." Then why don't you just say "Let's have the actors mumble." Why does a door slam have to sound like World War III? Why does a gunshot have to be bigger than any gunshot I've ever heard in my life? I want my music to be heard, and if you don't hear my scores, then I've failed. But I also don't want my music to be thrown out if the director feels that I'm taking attention away from the movie. The director is the captain of the ship. He can tell a writer to punch up the dialogue. He can make the lighting brighter. But when it gets to the music, the director is left saying something like "I want it to feel blue." What does that mean? Music isn't literal, it's dangerous. It can sneak up on you and do things. So you're fighting this psychological drama to get into the head of the captain of your ship, because he just can't do it. A director can control everything- except music. He understands it on the only level he should, an emotional one. And if the music doesn't work for him, it ain't working. There was a cue I did for The Thomas Crown Affair that had the room jumping up and down. But I said to John, "Look, if it doesn't work for you, it doesn't work. Let me do it differently." And I reached, and found what was missing for John so he could jump on the bandwagon. It's tough. The music is best if it's held down. It's more dangerous if it's loud.

DS: Your theme for Rocky is your most popular piece of music. What's it like to achieve that level of public consciousness?

BC: That kind of phenomenon happens when there's the coordination of people liking the movie and your music, and it being a hit. I've been fortunate to be on that ride. It didn't have to happen. But It did, and I'm thankful.

DS: You've scored films with a wide variety of styles, from jazz to Americana. Is there any style of music that you'd still like to explore?

BC: I just want to write pretty, melodic music. I haven't done something pretty and quiet in so long. But I've cut back anyway. I'm not doing as much. Most recently I did a picture called Winchell for Paul Mazursky and Inferno for Jean-Claude Van Damme. But I've felt a lack of scores like Slow Dancing In the Big City. The aggressive, macho, punch-in-the-face had its timespan in the 70's. And it's difficult to look away from a gift horse. But at least that punch-in-the-mouth stuff happened! And I can do the Rocky and Right Stuff styles when people want me to. But pretty, slow, sad music is what I want to do.

DS: Where do you want your music to stand in the grand scheme of film scores?

BC: It has to stand only as film music for sure. Remember, my opinion of it is not that high. It began with three Viennese composers, and Korngold is not Richard Strauss. He's not as good as him. Strauss' Salome is wonderful. Korngold, in his operas and his film scores are not to be said in the same breath as Richard Strauss. However, Korngold is probably one of the best film composers who ever lived! Franz Waxman, Max Steiner, they're great film composers. And if I could be part of a good group of film composers, then that would be nice. But there's a higher place that I have no illusions about reaching. There's a sophistication and aesthetic about composers who only write only for the music's sake. I don't follow the muse. I follow the film. I watch the opening of The Thomas Crown Affair, and the music feels a particular way, because that's the way I heard it. Is that a muse moment? Who knows, because it was inspired by the film, and that's what I do. I don't want it to sound like I'm putting film scoring down. I'm just being objective about the level that I'm at. Those pure composers are higher, better than me. I'm ripple, and they're big-time wine. But we still do the same things.

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario